Quantil Documentation

Declarative and Imperative Directives

Declarative and imperative are two different programming paradigms. Many articles can be found on the internet about these paradigms. In summary, a declarative program describes the desired end result whereas an imperative program describes the exact steps to achieve the result. Both paradigms have pros and cons and their respective suitable scenarios. A common use case of declarative programming is setting the parameters of some well-defined workflow. For example, when you order in a coffee shop, you may just tell the waiter "bring me a cup of coffee with sugar and milk." You don't need to give step-by-step instructions on how to make the coffee, including when to add sugar and milk, because you are pretty sure the staff knows the detailed procedure.

Serving and proxying content through HTTP is also a workflow well-defined by the network protocols. Therefore, the configuration of Nginx is mostly declarative and you don't need to care about how or when each directive is executed. For example, the directive add_header X-My-Data abc always; simply ensures the field X-My-Data: abc appears in the response header; proxy_pass https://www.my-upstream.com; tells the server to fetch the content from a designated upstream. These all seem quite straightforward, but things get interesting when you need to configure the workflow differently based on some conditions.

Configurations based on conditions

Let's return to the coffee ordering example. Suppose you also tell the waiter "add milk only if it's from brand M." An experienced waiter should know the milk inventory and, based on the availability of brand M, give a "flat" instruction "make a cup of coffee with sugar and milk" or "make a cup of coffee with sugar only" to the staff behind the counter. The instructions may even be as simple as "do code #1" or "do code #2" if they have predefined code names for different coffee-making processes.

Nginx supports conditions to be specified by the location and if directives. In addition, CDN Pro introduced elseif and else for more flexibility. The pair of curly braces following each of these directives defines a "context", which may be nested in an upper level context. The declarative directives in each context can be merged with the ones in the upper levels to obtain a "flat" configuration. When Nginx parses the configuration files at load time, it builds a lookup table of all the contexts and the corresponding flat configurations. For example, in the case of the following configuration:

server {

CONFIG_0

location /a { # context 1

CONFIG_1

}

location / { # context 2

CONFIG_2

if ($http_x_my_hdr) { # context 3

CONFIG_3

}

location /b { # context 4

CONFIG_4

}

}

}

The lookup table would resemble the following:

| Context | Merged "Flat" Configuration |

|---|---|

| 1 | Merge(CONFIG_0, CONFIG_1) |

| 2 | Merge(CONFIG_0, CONFIG_2) |

| 3 | Merge(CONFIG_0, CONFIG_2, CONFIG_3) |

| 4 | Merge(CONFIG_0, CONFIG_2, CONFIG_4) |

When a client request comes in, Nginx first tries to determine a context for the request, then applies the corresponding flat configuration to the remaining processing workflow, in a way similar to how the waiter converts your conditional order to a flat order. If the request matches multiple sibling contexts, the following rules ensure only one is selected:

- If there are multiple matching

ifblocks, pick the last one. Nginx does not merge configurations dynamically so the declarative directives in the otherifblocks are ignored; - If there are multiple matching

locationblocks, pick one based on this precedence; locationblocks have higher precedence than theifblocks.

Rule #1 above is probably the most confusing Nginx behavior to new users since it is different from most other programming languages. Therefore, we highly recommend the users not to put declarative directives in the if blocks and use the alternative methods described on this page if possible.

The "imperative" directives of the rewrite module

The if directive mentioned above is provided by the rewrite module. This module also supports a few important features like URL rewrite and variable creation and assignment. We have made some significant enhancements to the open source version and introduced a few new directives. Here is the list of directives from this module that can be used in CDN Pro: if, else, elseif, break, return, rewrite, set, and eval_func. The most important characteristic of the rewrite module is that its directives are executed sequentially - by the order they appear in the code like the imperative languages. However, they are all executed very early in the request processing workflow, before almost all the other directives except location. We are going to talk about some implications of this fact in the next section.

The directives set and eval_func provide means to assign values to variables. They can work with the if directive to set different values based on conditions. Given that most declarative directives support variables in their parameters, this provides a good way to alter the server's behavior based on conditions.

Timing of the declarative directives

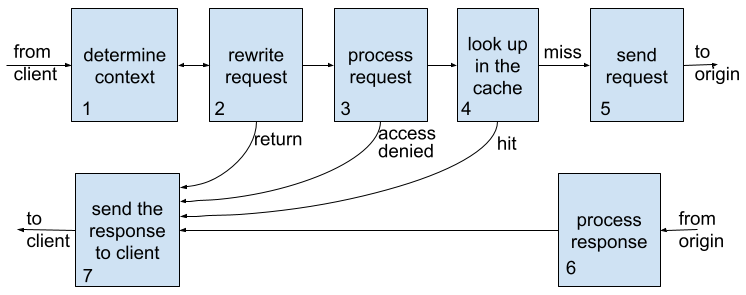

In principle, users do not need to care about the time when each declarative directive is executed, but having some knowledge about the timing can help you avoid a few common mistakes. In fact, the execution time of most directives can be easily determined by their functionalities in the request processing pipeline, which is sketched below with 7 stages.

For example, the directive add_header is executed when building the response header to the client in stage 7, and proxy_set_header is executed when building the request header to the upstream in stage 5. All the access control directives are executed in stage 3 and the rewrite module directives in stage 2.

Engineers familiar with imperative programming might forget that the location where a declarative directive appears in the configuration does not affect its execution time. Consider the following configuration:

allow 1.2.3.4;

deny all;

location /hello {

return 200 'Hello World!';

}

location / {

origin_pass my_origin;

}

Although the access control directives allow and deny are placed at the server level before the location blocks, they are executed after the location context is determined for the request, following all the rewrite module directives including return. Therefore, any request to "/hello" always receives the status code 200 and the access control directives are not executed.

A mistake often made by new users is attempting to put $upstream_* variables in the condition of an if directive, hoping to alter the behavior based on the origin's response. However, the if directive is executed very early in the request processing pipeline, way before the upstream request is even sent to the origin. At that time, only the variables extracted from the request are available and all the $upstream_* variable values are empty. The correct way to control behavior based on origin's response is to use the proprietary if() parameter we introduced to many directives. The condition in this parameter is evaluated when the directive is about to be executed. If this happens after the response is received (stages 6 and 7 in the flowchart), it can be useful to include the $upstream_* variables in the condition. For example, this is how to force removal of the "Cache-Control" header field from responses with status code 404 and cache for 1 hour:

origin_header_modify Cache-Control '' policy=overwrite if($upstream_status = 404);

proxy_cache_valid 404 1h;

Support of variables is a powerful feature of Nginx. Some variables are updated continuously during the request processing workflow. The value seen by each directive depends on its execution time. The most notable example is the variable $request_time, which returns the time elapsed since the request was received. Consider the following code snippet:

set $req_time $request_time;

add_header X-req-time-1 $req_time;

add_header X-req-time-2 $request_time;

New users may be surprised to see different values in the two response header fields. This is because set is executed early in the workflow, so it gets an earlier snapshot of $request_time and saves to the variable $req_time. add_header is executed later while building the response header to the client, so the value added to the header field X-req-time-2 will be larger. But do not expect it to be the total processing time of the request, because more time may be spent later to transfer the response body. In case of a large response, the value in the header can be significantly smaller than the total processing time.